Key takeaways

When coupon payments on shorter-term Treasury bonds exceed the interest paid on longer term bonds, the result is an inverted yield curve.

This occurred in 2022 and continues in 2023.

Some market observers consider a yield curve inversion a harbinger of economic recession.

Investors look for indicators that might offer insight into future economic trends. One potential signal considered by some to be a telltale sign is an “inverted yield curve,” when interest paid on shorter term U.S. government-issued bonds exceeds the interest rate on longer term bonds. While it may sound like an arcane event, an inversion of the yield curve is sometimes considered a warning signal for the U.S. economy. A yield curve inversion occurred in 2022 and continues in 2023.

What is an inverted yield curve?

The concept of the yield curve starts with bonds of different maturities and is often based on yields of U.S. Treasury securities. These are bonds of equal credit quality (all backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government) but with different maturities.

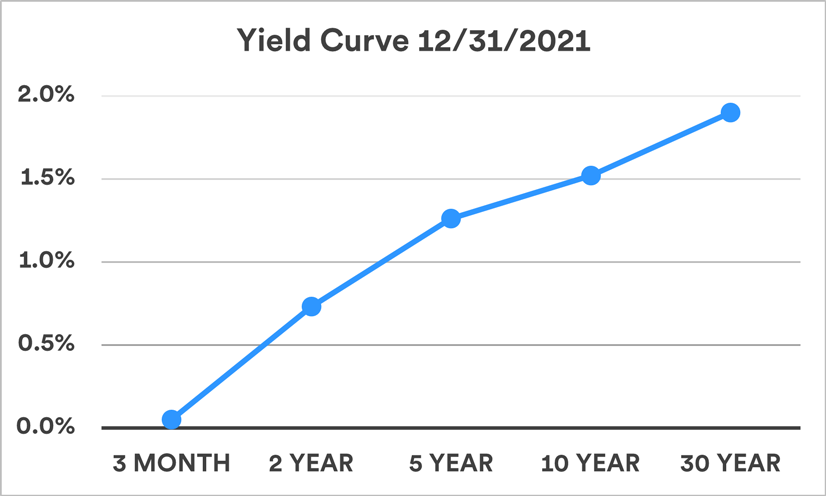

A simple way to view the yield curve is to look at current interest rates, or yields, paid by U.S. Treasury securities with maturities of three months, two years, five years, 10 years and 30 years. Investors typically expect to be rewarded with higher yields when they invest their money for longer periods of time. This is referred to as a normal yield curve, one where yields rise along the curve as bond maturities lengthen. The chart below depicts a normal, upward sloping yield curve among these five U.S. Treasury securities, depicting actual yields in the Treasury market at the end of 2021.1 At that time, the yield on 3-month Treasury bills stood at 0.05%, and moved progressively higher as maturities extended along the yield curve.

Source: U.S. Department of the Treasury

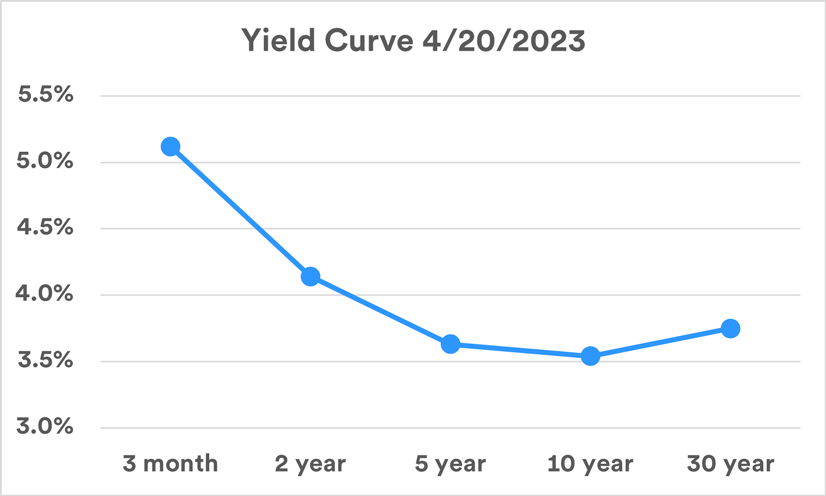

There are unusual circumstances where the yield curve “inverts.” The use of this term does not necessarily indicate that the slope moves from higher to lower when reading the chart from left to right. But it can mean that yields on some shorter-term securities are higher than those for longer-term securities.

In 2022, the yield curve first inverted on April 1 when comparing two of the key indicator rates along the curve – the 2-year Treasury note and 10-year Treasury note.1 After a short period of time, yields reverted to a normal curve, but an inversion between the 2-year and 10-year Treasuries occurred again in early July. In late October, the yield on the very short-term 3-month Treasury bill moved above that of the 10-year Treasury note. The inversion became more pronounced toward the end of 2022 and the spread widened in the opening months of 2023. Interest rates paid by 3-month Treasury bills are now more than 1.5% higher than those available from 10-year Treasury bonds.

Source: U.S. Department of the Treasury

Some analysts see this rare event as a key economic signal, with many speculating that it foretells a future recession. Rob Haworth, senior investment strategy director at U.S. Bank, believes the inversion of yields between 3-month and 10-year Treasury securities is particularly notable. “It represents a higher cost for corporations,” says Haworth. “With short-term rates so high, companies are increasingly reluctant to borrow, as it makes it more challenging to realize a payoff when investing the borrowed capital in new equipment and facilities or added employees.” Haworth indicates that this can be a precursor to a slowdown in economic activity.

Signs of a recession?

How reliable of a recession indicator is the inversion of 3-month and 10-year Treasury yields? “It’s hard to know for certain, but historically, when we see such a significant inversion, it typically points to a recession,” says Matt Schoeppner, senior economist, U.S. Bank. “Banks tend to start pulling back from lending in this type of environment, and higher interest rates also dampen consumer borrowing.”

Schoeppner adds that while these factors are potential harbingers of an economic downturn, it’s not yet a foregone conclusion. “While bank lending has tightened, it’s not clear that it’s happening at a pace that is indicative of a recession,” says Schoeppner.

Haworth says that markets, nevertheless, have already begun pricing in the prospects of a downturn. “Even without the inversion, there are expectations built into many economists’ projections that we’ll experience an economic contraction in 2023,” says Haworth. However, given that the economy continues to grow, albeit at a slower pace, investors may be looking for signs that a recession can be avoided in the near term.

Haworth says there are specific factors that bear watching to determine the direction of the economy in 2023. “We’ve seen a clear slowdown in the housing market, with higher mortgage rates making homes less affordable,” says Haworth. “Now we have to watch what’s happening with personal incomes.” He believes the key signals about future economic strength will come down to whether the labor market experiences a sustained uptick in layoffs that ultimately leads to rising unemployment. Recent data shows the unemployment rate at 3.5%, near a half-century low.2 To this point, the strength of the labor market has helped keep the economy on track.

The Federal Reserve’s interest rate influence

Beginning with the last recession, triggered by the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020, the Fed reduced the short-term federal funds target rate to near zero percent, which helped keep rates on short-term government debt securities low. As the first chart above (from 2021) shows, yields on the shortest-term government securities were near 0%. At the same time, the Fed began making monthly purchases of Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities, a step that helped moderate interest rates on the long end of the yield curve.

“Even without the inversion, there are expectations built into many economists’ projections that we’ll experience an economic contraction in 2023.”

Rob Haworth, senior investment strategy director at U.S. Bank

Once inflation emerged as a persistent concern in 2021, the Fed shifted its strategy. It eventually ended its bond purchases in March 2022 and began to reduce its more than $8 trillion in asset holdings. By playing less of a role in the broader bond market, one result could be that long-term interest rates move higher. In fact, interest rates rose significantly across the board in 2022. Yet after peaking at 4.25% in October, yields on 10-year Treasuries backed off, then topped 4% again in March before retreating again. News of two regional bank failures raised concerns in the market, driving more investors into bonds. Increased demand for bonds typically pushes interest rates lower, and yields on 10-year Treasuries have remained below 4% since the regional bank troubles occurred.

Short-term rates in the broader bond market tend to respond to the Fed’s strategy related to the target federal funds rate it controls. The Fed raised the fed funds rate from near 0% prior to March 2022 to the 4.74% to 5.00% range by March 2023. Since the Fed altered its strategy, yields on 3-month U.S. Treasury bills jumped, from 0.01% at the end of 2021 to higher than 5.0% today. More Fed rate hikes are expected in 2023, though Fed officials have indicated those increases will be more modest than what occurred in 2022. Even so, it could continue to have the effect of pushing short-term interest rates higher across the broader bond market. The Fed is likely to maintain elevated interest rates into 2024. Haworth believes that as the Fed sets monetary policy, it’s paying close attention to the impact on the bond market in the hopes of reestablishing a normal yield curve. He points out that the Fed has many tools available to try to influence yields at different maturities in order to effectively achieve its goals of cooling off inflation while avoiding a recession.

Where the economy goes from here

The outlook for the U.S. economy in 2023 has become a bit cloudier in recent months. After growing at a rate of 5.9% as measured by Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2021, the economy expanded by just 2.1% in 2022.3 The Fed’s money tightening measures are designed to temper economic growth with the aim of slowing inflation. The question now is whether the Fed can succeed in its inflation-fighting strategy without pushing the economy into a recession.

Haworth is watching how corporations react to the inverted yield curve. Most companies managed to maintain a strong financial position through 2022, but Haworth says corporate revenue and earnings will be under increasing pressure. “There is less of a payoff from capital spending in the current interest rate environment,” says Haworth. “This could ultimately be one factor driving the economy toward a recession.” Consumer spending is the other important factor affecting the economic outlook. While it remained solid in the opening months of 2023, prospects for the immediate future are less certain.

Check-in with your wealth planning professional to make sure you’re comfortable with your current investments and that your portfolio remains consistent with your long-term financial goals.

Tags:

Related articles

How are rising interest rates impacting bond prices in 2022?

With the Federal Reserve increasing interest rates in an effort to get inflation under control, what opportunities does this create for bond investors?

How to put cash you’re keeping on the sidelines back to work in the market

Don’t let market volatility and an uncertain economic outlook derail your disciplined investing strategy.